Cambridge! Somerville! Boston! Allston Rock City! Late notice, but I’m guest DJing at Tourfilter‘s monthly residency at River Gods, just outside Central Square, Cambridge this week: Thursday, September 16th, and the festivities start at 9 pm. Same drill as last time: my playlist is composed entirely of songs from artists with shows lined up for the Boston area in the next month or so. And the fall concert calendar looks fantastic.

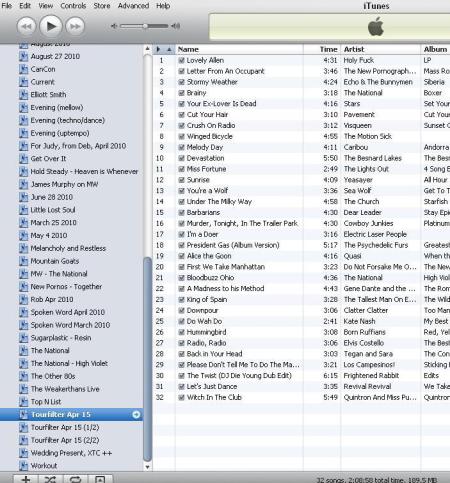

UPDATED: (Friday, September 17th) Here’s the full playlist:

01 Guided By Voices, “I Am A Scientist” Friday, November 5th at Paradise Rock Club

02 The Motion Sick, “Winged Bicycle” Saturday, September 18th at TT the Bear’s

03 Great Big Sea, “When I’m Up (I Can’t Get Down)” Friday, September 17th at Orpheum Boston

04 Screaming Females, “I Don’t Mind It” Tuesday, September 28 TT the Bear’s Place

05 Me First and the Gimme-Gimmes, “The Rainbow Connection (Muppets cover)” Thursday, October 21st at Paradise Rock Club

06 Superchunk, “Hyper Enough” Tuesday, September 21st at Royale Boston

07 James, “Laid” Saturday, September 25th at Paradise Rock Club

08 Belle and Sebastian, “Judy and the Dream of Horses” Friday, October 15th at Wang Theatre

09 Frightened Rabbit, “Swim Until You Can’t See Land” Friday, October 29th at Paradise Rock Club

10 Do Not Forsake Me Oh My Darling, “First We Take Manhattan” (Leonard Cohen cover) Friday, September 24th at Church

11 Sufjan Stevens, “Chicago” Wednesday, November 10th at Orpheum Theatre

12 Born Ruffians, “What to Say” Wednesday, September 29th at The Middle East

13 Teenage Fanclub, “Your Love is the Place Where I Come From” Saturday, September 25th at Royale Boston

14 Swans, “Love Will Tear Us Apart” (Joy Division cover) Thursday, September 30th at Middle East Downstairs

15 Stars, “This Charming Man” (Smiths cover) Thursday, September 23rd at House of Blues Boston

16 Mates of State, “Get Better” Sunday, September 26th at Paradise Rock Club

17 Sea Wolf, “You’re a Wolf” Tuesday, September 21st at Middle East Upstairs

18 Cake, “Short Skirt, Long Jacket” Saturday, September 18th at Orpheum Theatre

19 Oranjuly, “I Could Break Your Heart” Thursday, September 16th at Great Scott

20 Pavement, “Stereo” Saturday, September 18th at Agannis Arena

21 Of Montreal, “Coquet Coquette” Thursday, September 16th at House of Blues Boston

22 Broken Social Scene, “Texico Bitches” Friday, September 17th at House of Blues Boston

23 Built to Spill, “You Were Right” Friday, October 1st at Paradise Rock Club

24 Sleigh Bells, “Tell ‘Em” Tuesday, September 28th at Orpheum Theatre

25 The Xx, “VCR (Matthew Dear remix)” Sunday, October 3rd at Orpheum Theatre

26 Holy Fuck, “Lovely Allen” Sunday, September 19th at Paradise Rock Club

27 Gary Numan, “Cars” Thursday, October 22nd at Paradise Rock Club

28 Caribou, “Odessa” Sunday, September 19th at Paradise Rock Club

29 Ratatat, “Drugs” Wednesday, September 29th at Paradise Rock Club

30 LCD Soundsystem, “Dance Yrself Clean” Tuesday, September 28th at Orpheum Theatre

Image: River Gods by brixton, used here under its Creative Commons license.